The year of 2020 came with many challenges not least for our heritage and cultural venues in Brecon and for the people who enjoy these spaces. However one of the positives of the year was a visual and sound recording in Brecon Cathedral of a solo violinist playing a piece of music entitled The Cresset Stone by composer Hilary Tann.

Hilary was especially drawn to the contrast between the solid, dark, cold, unmoving nature of the stone and the flickering, shape-shifting, transient, brightness of the flame. The seed idea for the composition came from this experience. She returned to her college to teach for the autumn term and then had time to write it before the winter term began. The stone sections are meditative in nature, and low on the instrument; some pay homage to the solo literature of the Japanese bamboo flute, the shakuhachi. The flame sections rise up through the registers and there are two sections containing many violin harmonics where the flame seems to dance. The Kyrie-inspired phrases acknowledge that this alchemy between the stone and flame is taking place within an ancient stone cathedral, a place of worship and prayer. As the piece concludes, the flame has died down, but the stone itself remains warm from the memory of the encounter. Hilary says “Yes, the piece is about stone and light, but it is also a meditation about a kind of love.”

Violinist Mary Hofman’s collaboration with Hilary Tann started when she commissioned a work from her in 2019 to be performed as part of what was planned to be a Beethoven project in music clubs across Wales in 2020. The work First Light was a beautiful meditation on Beethoven's tenth violin sonata. They were due to perform the piece across Wales in 2020 and had a recording of it with Ty Cerdd that was due to be released in September 2020. None of these things were able to happen and the idea for The Cresset Stone recording came about.

The filmed recording of the piece in the physical context was something they knew could be something beautiful and powerful. The hope that it might be possible to light the 1,000 year old stone and have this central to the performance was enabled by the Dean of Brecon cathedral and Stephen Power, the director of music at the Cathedral.

Mary Hofman, when interviewed said “It was an extraordinary experience to play in the cathedral alone (just myself and two people filming): the flickering of the light on the chisel marks in the stone so that you could almost see the hands of the people who carved them; the extraordinary acoustics; the sense of smallness both in space and in history. It felt as though the music took on layers and layers of extra meaning. It is a piece which is all about light in darkness, stone and movement. It feels particularly appropriate to this time.”

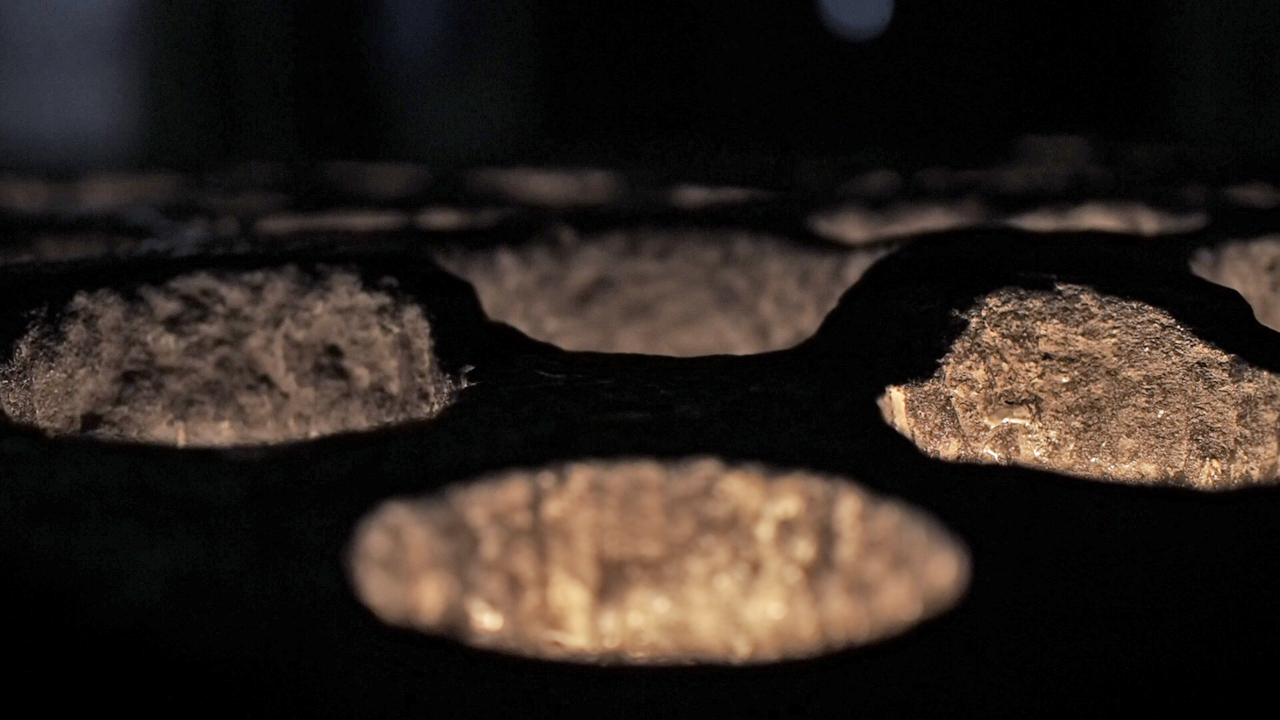

The word 'cresset' is derived from the old French 'craicet', 'craisset' or 'cresset', a cup of metal or other material fastened to a pole to form a portable lantern. A 'cresset stone' was a flat stone with cup-shaped hollows, each being used to hold a quantity of tallow and a wick, which were burned to produce light. These were lit in the Church at midnight, when the Monks came to matins. It was also common to find such stones near doorways or corners where people had to frequently pass each other, and in the Monk’s' Dorter or dormitory.

This was a common method of lighting churches in medieval times. Although there are some thirteen cresset stones remaining in various parts of England, the Brecon cresset stone is the only one so far known in Wales, and is the finest yet discovered. The 15cm deep stone has thirty ‘cups’ arranged in five parallel rows, with six cups in each row (14 more cups than at Carlisle Cathedral, where the largest cresset stone previously discovered is located). It is made of native stone, which is laminated in two places, probably as a result of blows.